Association Between Maternal Malaria Prevention and the Occurrence of Malaria Parasites Among Mothers and Their Newborns at the University of Medical Sciences Teaching Hospital, Akure

Authors

##plugins.themes.bootstrap3.article.main##

Abstract

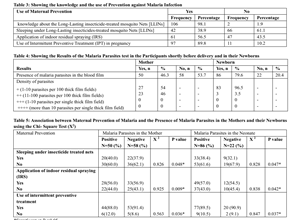

Background: Malaria in pregnancy is a public health problem in tropical countries like Nigeria where it is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Several strategies have been put in place to control its occurrence in pregnancy but despite all these the prevalence has persistently remained high in the tropics. Aims & Objectives: This study is aimed at assessing the occurrence of malaria parasites in the mothers and the newborns when established preventive measures such as insecticide treated nets, residual indoor spraying and intermittent preventive treatment are used. Methodology: The study utilized cross-sectional descriptive survey design to recruit 108 mothers and 108 neonates who booked and delivered at the University of Medical Sciences Teaching Hospital, Akure. Their blood samples were collected and assessed for the presence and density of malaria parasites using their thick films by trained research assistants and certified laboratory scientists. Information about the participants socio-demographic characteristics, use of malaria prevention methods, Obstetrics and clinical characteristics of the mothers and their newborns were also obtained from their clinical records. Data obtained was analyzed using SPSS Windows 25. Frequency tables were obtained from relevant variables, Chi Square test was used to obtain the association between maternal prevention and the presence of parasites in the mothers and the newborns and a Multi-variable logistic regression was used to predict the main method of prevention with lower risk of the occurrence of malaria parasites. Significant value was set at P<0.05. Results: The participants were mostly primigravidae who had more than four antenatal visits and also had good knowledge of the use of the long- lasting insecticide treated nets. However, only 42 (38.9%) actually slept under the nets. Many had the opportunity of having intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy, 97 (89.8%). Among the women, 50 (46.3%) had malaria parasites while 86 (79.8%) of the newborns had malaria parasites. Out of the 50 mothers who had malaria parasites, 30 (60.0%) did not sleep under an insecticide treated net, this was statistically significant [X2=0.826, P=0.048]. Similarly, 53 (61.6%) of the newborns with malaria parasites were delivered by mothers who did not sleep under the insecticide treated nets, this was also statistically significant [X2=0.828, P=0.047]. Out of these 50 mothers, 22 (44.0%) did not apply indoor residual spraying which was found to be statistically significant in contributing to the presence of the parasites [X2= 0.925, P=0.009]. Also 37(43.0%) of these neonates were delivered by the mothers who did not apply indoor residual spraying which was also statistically significant [ X2=0.838, P=0,042]. The use of intermittent preventive treatment was found to significantly reduce the presence of malaria parasites in the mothers [X2=0.563, P=0.036] and the newborns [X2=0.847, P=0.037]. Conclusion: This study showed that the use of insecticide treated nets, residual spraying or the use of intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy can significantly reduce the presence and the density of malaria parasites in the mother and the neonates though some still had the parasites. Therefore, possible combination of these methods of prevention may be useful to achieve complete absence of malaria parasites in the mothers and their newborns.

##plugins.themes.bootstrap3.article.details##

Copyright (c) 2025 Theresa Azonima Irinyenikan, Emmanuel Olaseinde Bello, Bamidele Jimoh Folarin, Rosena Olubanke Oluwafemi, Ismaila Sani

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Creative Commons License All articles published in Annals of Medicine and Medical Sciences are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

[1] World Health Organization. “Implementing malaria in pregnancy programs in the context of World Health Organization recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience,” WHO 2018 Link: https://bit.ly/3xp61di

[2] Omer SA, Idress K, Adam I, Abdelrahim M, Nouredein A, Abdelrazig A, Elhassan M, Sulaiman S. Placental malaria and its effect on pregnancy outcomes Sudanese women from Blue Nile State. Malar J. 2017;16(1):374.

[3] Huynh BT, Cottrell G, Cot M, Briand V. Burden of malaria in early pregnancy: a neglected problem? Clin Infect Dis. 2015; 60:598–604.

[4] Oyeniran AA, Bello FA, Oluborode B, Awowole I, Loto OM, Irinyenikan TA, et al. Narratives of women presenting with abortion complications in Southwestern Nigeria: a qualitative study. Plos One. 2019; 14: e0217616.

[5] Taylor SM, Ter Kuile FO. Stillbirths: the hidden burden of malaria in pregnancy. Lancet Glob Health. 2017; 5: e1052–1053.

[6] Menéndez C, Bardají A, Sigauque B, Romagosa C, Sanz S, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnant women in the context of insecticide treated nets delivered through the antenatal clinic. PLoS ONE. 2008; 3(4): e1934. https:// doi. org/10. 1371/ journ al. pone. 000193.

[7] Eisele TP, Larsen D, Steketee RW. Protective efficacy of interventions for preventing malaria mortality in children in plasmodium falciparum endemic areas. Int J Epidemiol. 2010; 39:88–101.

[8] WHO. Policy brief for the implementation of intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy using sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (IPTp-SP). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

[9] Orobaton N, Austin AM, Abegunde D, Ibrahim M, Mohammed Z, Abdul-Azeez J, et al. Scaling-up the use of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine for the preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy: results and lessons on scalability, costs and programme impact from three local government areas in Sokoto State, Nigeria. Malar J.; 2016 (15): 533

[10] Falade CO, Yusuf B, Fadero FF, Mokuolu OA, Hamer DH and Salako LA. Intermittent preventive treatment with sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine is effective in preventing maternal and placental malaria in Ibadan, southwestern Nigeria. Malaria Journal 2007, 6(88).

[11] N’Guessan R, Corbel V, Akogbéto M, Rowland M. Reduced efficacy of insecticide-treated nets and indoor residual spraying for malaria control in pyrethroid resistance area, Benin. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13(2):199-206. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1302.060631]

[12] Takken W, Knols BG. Malaria vector control: Current and future strategies. Trends Parasitol2009;25(3):101-104. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2008.12.002]

[13] Chanda E, Masaninga F, Coleman M, et al. Integrated vector management: The Zambian experience. Malar J 2008; 7:164. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-7-164].

[14] World Health Organization. World malaria report 2022. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022.

[15] World Health Organization. World Malaria Report. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2021.

[16] Malaria consortium Malaria control Nigeria: State fact sheets (2016). Link: https://bit.ly/3fG8B8K

[17] Iwuchukwu IC, Vincent CN. Studies on prevalence of malaria and its adverse fetal outcomes in Federal Medical Centre (FMC), Owerri, IMO State, Nigeria. Arch Community Med Public Health 2021; 7(2): 151-163. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.17352/2455-5479.000156

[18] Bardaj A, Sigauque B, Sanz S, Maixenchs M, Ordi J Aponte JJ, et al. Impact of malaria at the end of pregnancy on infant mortality and morbidity. J Infect Dis 2011; 203(5):691–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/ infdis/jiq049 PMID: 21199881

[19] Saba N, Sultana A, Mahsud I. Outcome and complications of malaria in pregnancy. Gomal J Med Sci 2008; 6(2):98–101.

[20] Van Geertruyden JP, Thomas F, Erhart A, d’Alessandro U. The contribution of malaria in pregnancy to perinatal mortality. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71(2):35–40. PMID: 15331817

[21] Ruhago GM, Mujinja PG, Norheim OF. Equity implications of coverage and use of insecticide treated nets distributed for free or with co-payment in two districts in Tanzania: a cross-sectional comparative household survey. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10(1):29.

[22] Rosero-Bixby L. Spatial access to health care in Costa Rica and its equity: a GIS-based study. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(7):1271–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00322-8.

[23] Brabin BJ, Rogerson SJ, 2001. The epidemiology and outcomes of maternal malaria. Duffy PE, Fried M, eds. Malaria in Pregnancy Deadly Parasite, Susceptible Host. London and New York: Taylor and Francis, 27–52.

[24] Hviid L, Staalsoe T, 2004. Malaria immunity in infants: a special case of a general phenomenon? Trends Parasitol 20: 66–72.

[25] Murungi LM, Sondén K, Odera D, Oduor LB, Guleid F, Nkumama IN, Otiende M, Kangoye DT, Fegan G, Färnert A, Marsh K, Osier FHA. 2017. Cord blood IgG and the risk of severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria in the first year of life. Int J Parasitol 47:153–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.09.005

[26] Khattab A, Chia Y-S, May J, Le Hesran J-Y, Deloron P, Klinkert M-Q. 2007. The impact of IgG antibodies to recombinant Plasmodium falciparum 732var CIDR-1alpha domain in mothers and their newborn babies. Parasitol Res 101:767–774. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-007-0548-1

[27] Lengeler C. Insecticide-treated bed nets and curtains for preventing malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD000363.

[28] WHO. Global technical strategy for malaria 2016–2030. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. http://www.who.int/malaria/ areas/global_technical_strategy/en/

[29] Kayentao K, Garner P, Van Eijk AM, Naidoo I, Roper C, Mulokozi A, et al. Intermittent preventive therapy for malaria during pregnancy using 2 vs 3 or more doses of sulfadoxine pyrimethamine and risk of low birth weight in Africa. Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012.

[30] Conteh L, Sicuri E, Manzi F, Hutton G, Obonyo B, Tediosi F, et al. The cost effectiveness of intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in infants in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE. 2010.

[31] West PA, Protopopoff N,Wright A, Kivaju Z, Tigererwa R, Mosha FW, et al. Indoor residual spraying in combination with insecticide treated nets alone for protection against malaria: a cluster randomized trial in Tanzania. PLoS Med. 2014.

[32] Pluess B, Tanser FC, Lengeler C, Sharp BL. Indoor residual spraying for preventing malaria. Cochrane Libr. 2010.